The United States’ civic narrative – the pursuit of the American Experiment in liberal democratic self-government – is the glue that holds it together. Without it, the federation has always been vulnerable to collapse because it is in reality Balkanized federation of rival regional cultures – “stateless nations” if you will – that otherwise agree on very little.

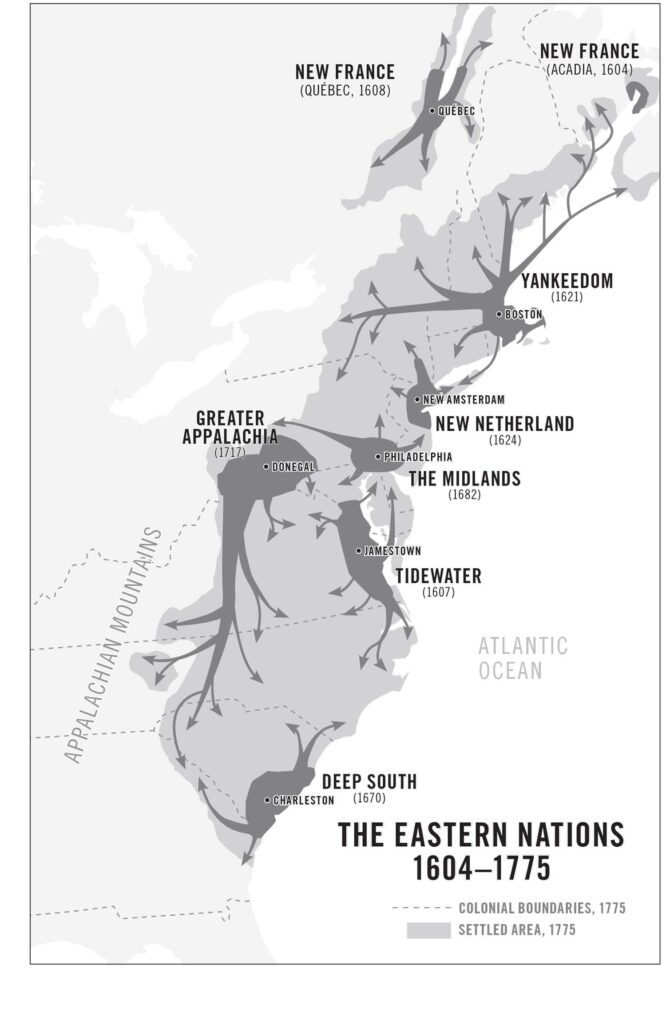

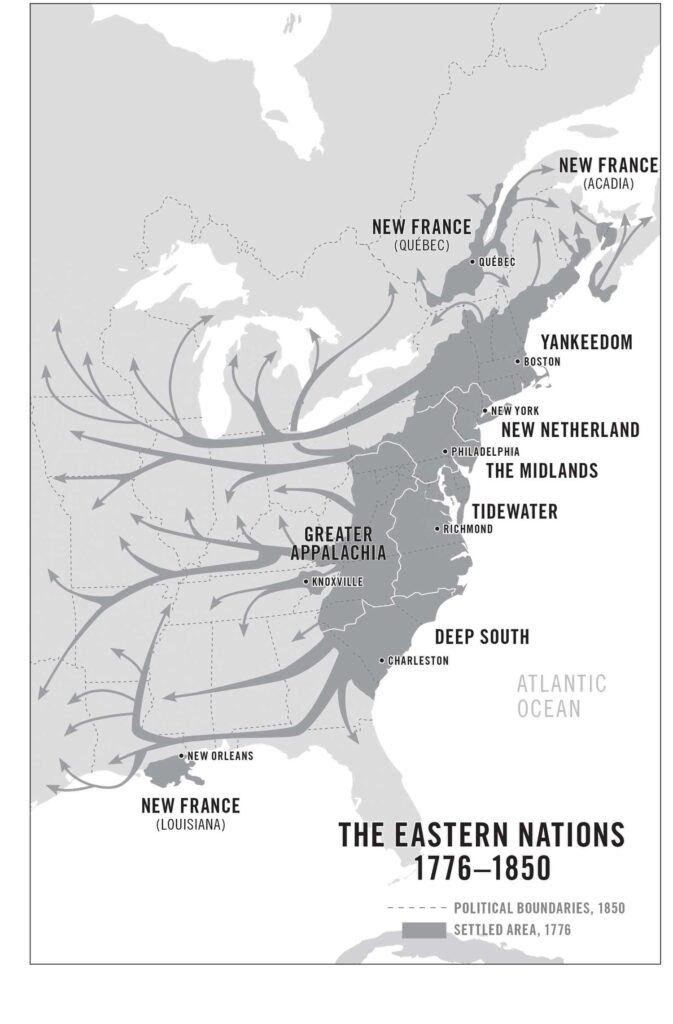

As described in American Nations, our true regional fissures can be traced back to the contrasting ideals of the distinct European colonial cultures that first took root on the eastern and southern rims of what is now the United States, and then spread across much of the continent in mutually exclusive settlement bands, laying down the institutions, symbols and cultural norms later arrivals would encounter and, by and large, assimilate into. (Academically, this work is built on the foundations of the late cultural geographer Wilbur Zelinsky’s Doctrine of First Effective Settlement, and is described for a scientific audience in this paper.)

The fissures between these regional cultures – the tectonic plates of our history, culture and politics – rarely respect state or even international boundaries, spilling over (or, in some cases, from) what are now the Canadian and Mexican federations. They are described in detail in American Nations, but here is a thumbnail sketch of each:

YANKEEDOM

Founded on the shores of Massachusetts Bay by radical Calvinists as a new Zion, Yankeedom has, since the outset, put great emphasis on perfecting earthly civilization through social engineering, denial of self for the common good and assimilation of outsiders. It has prized education, intellectual achievement, communal empowerment and broad citizen participation in politics and government, the latter seen as the public’s shield against the machinations of grasping aristocrats and other would-be tyrants. Since the early Puritans, it has been more comfortable with government regulation and public-sector social projects than many of the other nations, who regard the Yankee utopian streak with trepidation.

NEW NETHERLAND

Established by the Dutch at a time when the Netherlands was the most sophisticated society in the Western world, New Netherland has always been a global commercial culture – materialistic, with a profound tolerance for ethnic and religious diversity and an unflinching commitment to the freedom of inquiry and conscience. Like 17th-century Amsterdam, it emerged as a center of publishing, trade and finance, a magnet for immigrants and a refuge for those persecuted by other regional cultures, from Sephardim in the 17th century to gays, feminists and bohemians in the early 20th. Unconcerned with great moral questions, it nonetheless has found itself in alliance with Yankeedom to defend public institutions and reject evangelical prescriptions for individual behavior.

THE MIDLANDS

America’s great swing region was founded by English Quakers, who believed in humans’ inherent goodness and welcomed people of many nations and creeds to their utopian colonies like Pennsylvania on the shores of Delaware Bay. Pluralistic and organized around the middle class, the Midlands spawned the culture of Middle America and the Heartland, where ethnic and ideological purity have never been a priority, government has been seen as an unwelcome intrusion and political opinion has been moderate. An ethnic mosaic from the start – it had a German, rather than British, plurality at the time of the Revolution – it shares the Yankee belief that society should be organized to benefit ordinary people, though it rejects top-down government intervention.

TIDEWATER

Built by the younger sons of southern English gentry in the Chesapeake country and neighboring sections of Delaware and North Carolina, Tidewater was meant to reproduce the semi-feudal society of the countryside they’d left behind. Standing in for the peasantry were indentured servants and, later, slaves. Tidewater places a high value on respect for authority and tradition, and very little on equality or public participation in politics. It was the most powerful of the American nations in the 18th century, but today it is in decline, partly because it was cut off from westward expansion by its boisterous Appalachian neighbors and, more recently, because it has been eaten away by the expanding federal halos around D.C. and Norfolk.

GREATER APPALACHIA

Founded in the early 18th century by wave upon wave of settlers from the war-ravaged borderlands of Northern Ireland, northern England and the Scottish lowlands, Appalachia has been lampooned by writers and screenwriters as the home of hillbillies and rednecks. It transplanted a culture formed in a state of near-constant danger and upheaval, characterized by a warrior ethic and a commitment to personal sovereignty and individual liberty. Intensely suspicious of lowland aristocrats and Yankee social engineers alike, Greater Appalachia has shifted alliances depending on who appeared to be the greatest threat to their freedom. It was with the Union in the Civil War. Since Reconstruction, and especially since the upheavals of the 1960s, it has joined with Deep South to counter federal overrides of local preference.

DEEP SOUTH

Established by English slave lords from Barbados, Deep South was meant as a West Indies–style slave society. This nation offered a version of classical Republicanism modeled on the slave states of the ancient world, where democracy was the privilege of the few and enslavement the natural lot of the many. Its caste systems smashed by outside intervention, it continues to fight against expanded federal powers, taxes on capital and the wealthy, and environmental, labor and consumer regulations.

EL NORTE

The oldest of the American nations, El Norte consists of the borderlands of the Spanish American empire, which were so far from the seats of power in Mexico City and Madrid that they evolved their own characteristics. Most Americans are aware of El Norte as a place apart, where Hispanic language, culture and societal norms dominate. But few realize that among Mexicans, norteños have a reputation for being exceptionally independent, self-sufficient, adaptable and focused on work. Long a hotbed of democratic reform and revolutionary settlement, the region encompasses parts of Mexico that have tried to secede in order to form independent buffer states between their mother country and the United States.

THE LEFT COAST

A Chile-shaped nation wedged between the Pacific Ocean and the Cascade and Coast mountains, the Left Coast was originally colonized by two groups: New Englanders (merchants, missionaries and woodsmen who arrived by sea and dominated the towns) and Appalachian midwesterners (farmers, prospectors and fur traders who generally arrived by wagon and controlled the countryside). Yankee missionaries tried to make it a “New England on the Pacific,” but were only partially successful. Left Coast culture is a hybrid of Yankee utopianism and Appalachian self-expression and exploration – traits recognizable in its cultural production, from the Summer of Love to the iPad. The staunchest ally of Yankeedom, it clashes with Far Western sections in the interior of its home states.

THE FAR WEST

The other “second-generation” nation, the Far West occupies the one part of the continent shaped more by environmental factors than ethnographic ones. High, dry and remote, the Far West stopped migrating easterners in their tracks, and most of it could be made habitable only with the deployment of vast industrial resources: railroads, heavy mining equipment, ore smelters, dams and irrigation systems. As a result, settlement was largely directed by corporations headquartered in distant New York, Boston, Chicago or San Francisco, or by the federal government, which controlled much of the land. The Far West’s people are often resentful of their dependent status, feeling that they have been exploited as an internal colony for the benefit of the seaboard nations. Their senators led the fight against trusts in the mid-20th century. Of late, Far Westerners have focused their anger on the federal government, rather than their corporate masters.

NEW FRANCE

Occupying the New Orleans area and southeastern Canada, New France blends the folkways of ancien régime northern French peasantry with the traditions and values of the aboriginal people they encountered in northeastern North America. After a long history of imperial oppression, its people have emerged as down-to-earth, egalitarian and consensus driven, among the most liberal on the continent, with unusually tolerant attitudes toward gays and people of all races and a ready acceptance of government involvement in the economy. The New French influence is manifest in Canada, where multiculturalism and negotiated consensus are treasured.

FIRST NATION

First Nation is populated by native American groups that generally never gave up their land by treaty and have largely retained cultural practices and knowledge that allow them to survive in this hostile region on their own terms. The nation is now reclaiming its sovereignty, having won considerable autonomy in Alaska and Nunavut and a self-governing nation state in Greenland that stands on the threshold of full independence. Its territory is huge – far larger than the continental United States – but its population is less than 300,000, most of whom live in Canada.

American Nations told the history of these eleven regional cultures. For analytical purposes, the U.S. also comprises enclaves of two other regions whose center of gravity lies outside the continental North American landmass. South Florida is part of Spanish Caribbean, Spain’s maritime cultural space in the Caribbean basin, a distinct culture from El Norte with an epicenter in Havana and including today’s Puerto Rico and Dominican Republic. Hawaii is one of the last places colonized by the great Pacific navigators who created Greater Polynesia, which encompasses French Polynesia, the Cook Islands, Samoa, and Tonga. The island of Newfoundland (but not Labrador) has a distinct settlement history and culture separate from other parts of Canada, a confederation it only begrudgingly joined in 1949. (The District of Columbia is a federal creation and does not belong to any of these regional cultures.) Researchers using this model should be aware that two U.S counties are shared equally between settlement cultures: Cook County, Illinois (Yankeedom/Midlands) and Orleans Parish, Louisiana (New France/Deep South.) We’ve also created tools to show the proportion of each state’s population that lies in a given region today, as well as in 1900 and 1950.

Throughout the colonial period and the Early Republic, these rival nations saw themselves as competitors – for land, capital and other settlers – and even as enemies, taking opposing sides in the American Revolution, the War of 1812 and the Civil War. The fissures can be seen in the geography of the key pre-secession votes in Congress, the Culture Wars of the 1960s, indices of violence and disease, COVID-19 vaccination and death rates, and most every hotly contested presidential election in our history. They are reflected in linguists’ maps of American dialects, cultural geographers’ maps of material culture dissemination, Census Bureau-derived maps of where the great 19th and early 20th century immigrants did and did not go; and even the maps of historic reproductive clustering generated from the cotton swabs millions of Americans have sent to Ancestry.com. Nations Apart, a sequel to American Nations, published in late 2025, shares this kind of analysis.

Understanding the continent’s true regional geography is essential to understanding the U.S. and how to strengthen the bonds binding it together. This is one component of the work we do at Nationhood Lab.